To be listed on the CAMPOSOL TODAY MAP please call +34 968 018 268.

Guidelines for submitting articles to La Manga Club Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing La Manga ClubToday.com to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

La Manga Club Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on La Manga Club Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@lamangaclubtoday.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb

History of Murcia, part 6

History of Murcia, 18th century to Modern Murcia

The History of Murcia Capital is written in 6 parts. To access the other sections, click below:

Part 1, Prehistoric Murcia, Click Prehistoric Murcia

Part 2, Of Romans and Visigoths, Click Romans and Visigoths

Part 3,Moors and Mursiya, Click Mursiya is born

Part 4,Mediaeval Murcia, Click Mediaeval Murcia

Part 5,From 16th to 18th Century, Click Murcia 16th to 18th Century

Part 6, From the end of the 18th Century to the beginning of the 21st, 18th to 21st Centuries

Murcia, From the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 21st.

At the end of the 18th century and the start of the 19th, Murcia had to face another wave of disasters. The problem of an imbalance between the food supply and the population arose again, and the pain of hunger brought into sharp focus the economic problems and social ills that had lain under the surface of Murcia’s growth over the previous hundred years.

At the end of the 18th century and the start of the 19th, Murcia had to face another wave of disasters. The problem of an imbalance between the food supply and the population arose again, and the pain of hunger brought into sharp focus the economic problems and social ills that had lain under the surface of Murcia’s growth over the previous hundred years.

A series of epidemics, floods and droughts again ravaged the poorer population, who at the same time had no option but to stoically accept the high prices of cereals and other basic foodstuffs, the irregular crop yields and the natural disasters.

On top of this the war of independence against Napoleon’s French armies (1808-14) further reduced Murcia’s active population. French troops entered the city in 1810, and the city was sacked. In 1812 they returned, and there was a bloody confrontation in the Calle San Nicolás.

It was during the war that the Courts of Cádiz introduced the Constitution of 1812, with Murcia accepting the document on 24th July of that year. This meant a break from the old régime and laid down the foundations of a more modern society. It also meant an acceptance of reformist principles and the triumph of the ideas of the French Revolution.

The written Constitution, though, was imposed on a largely illiterate population, a clergy violently opposed to liberalism and small groups of people in power who were desperate to retain their privileges. All of this made it inevitable that the Constitution would ultimately fail.

When it did so, absolute monarchy returned, this time in the shape of Fernando VII, and the schism was opened between absolutists and liberals. This conflict would dominate the first half of the nineteenth century throughout Spain.

Liberals and Absolutists: two incompatible philosophies

In 1820, the King was obliged to sign the 1812 Constitution by the Pronouncement of Riego, and the repercussions were felt in Murcia, where a horde of peasants from the Huerta, led by Regato and Romero Alpuente, stormed the city and freed all political prisoners.

The liberal government fell in 1823 after the “Invasion of the 100,000 Sons of San Luis”, and Absolutism returned to Spain, with Murcia being invaded by General Molitor.

Liberalism didn’t make its reappearance in Murcia until the death of Fernando VII in 1833. Until then the liberals had been in exile, and there was an atmosphere of social terror and religious fervor.

Signs of hope following Fernando’s death included the liberal leanings of the new Regent, María Cristina, who hoped to consolidate the stability of the Crown by moderately embracing liberal ideas in order for her daughter, Isabel II, to reign safely without threat from the Carlists, who defended the principles of absolutism.

The country was in chaos, as were most others in western Europe at the time: social terror continued to prevail, landowners lived in fear of populist violence, the bitter experiences of previous decades had left their mark, and in this climate the State made a pact with the liberal gentry to close off any possible road back to the régime of the past. Landed estates were abolished, as were the monopolies of town governments in the hands of a chosen few with almost feudal privileges.

In 1833 Francisco Javier de Burgos divided Spain administratively into provinces. Murcia became the capital of the Region of Murcia, which included not only the province of Murcia but also Albacete.

Urban reforms and economic growth in the second half of the 19th century

Isabel II visited Murcia in 1862 to perform the official opening of the railway and the Teatro de los Infantes, which is nowadays known as the Teatro Romea and re-opened in 2012 following a complete overhaul, ( Click Teatro Romea.). This was one of various examples of urban planning taking place on land repossessed from convents and monasteries.

Isabel II visited Murcia in 1862 to perform the official opening of the railway and the Teatro de los Infantes, which is nowadays known as the Teatro Romea and re-opened in 2012 following a complete overhaul, ( Click Teatro Romea.). This was one of various examples of urban planning taking place on land repossessed from convents and monasteries.

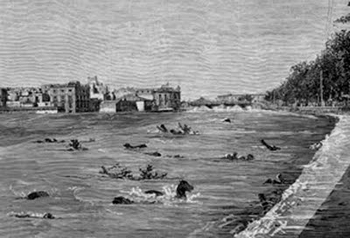

In 1879 Alfonso XII made a visit following the tragic Santa Teresa flood in October of that year, which led to the deaths of over 1,000 people in the city and the Huerta. Some villages, such as Nonduermas, were completely destroyed by the flood, and it is reported that in one ferocious downpour 24 inches of rain fell in an hour. ( Click, Riada de Santa Teresa)

The level of the river rose over ten metres, and it broke its banks in the city centre, while in Orihuela the floodwater reached the first floor of the buildings in the centre.

Despite all the setbacks, the century was marked by the growth of Murcia into a modern city, thanks to the creation of the Town Hall, the Floridablanca Park and the Casino, among many other urban projects.

Despite all the setbacks, the century was marked by the growth of Murcia into a modern city, thanks to the creation of the Town Hall, the Floridablanca Park and the Casino, among many other urban projects.

Reservoirs were built in the mountains upstream, reducing the risk of future flooding having effects as severe as those of 1879, and the removal of the old city walls allowed the centre to expand. The city began to take on the shape we know today.

In 1867 gas street lighting was extended to the whole of the city, and in 1893 Isaac Peral set up the first electric lighting factory in Murcia. Here he continued to work on more inventions following his famous submarine, ( Click Isaac Peral Submarine) some of which were carried on into the future (he patented an electric lift) while others weren’t (the electric machine-gun never really got off the ground).

A free University was founded, which later became the official University of Murcia in 1915.

A free University was founded, which later became the official University of Murcia in 1915.

Economically, Murcia benefited from the introduction of a complex cycle of crop rotation, involving the growing of cereals, leaf vegetables and root vegetables, especially potatoes. When the industrial revolution finally hit the Region with full force in the 1880s, its innovative and financial strength was inevitably channeled into the food industry.

The First Republic and the Canton of Murcia

The dominance of the conservative bourgeoisie caused social tension, and eventually Isabel II was forced into exile. There followed six years of revolution (1868-73) and, in Murcia, the constitution of revolutionary juntas.

In this climate of uncertainty and instability, the Republicans of Murcia, formed by the middle classes and sectors of the petit bourgeoisie, decided to accelerate their reform program and embark on a federalist adventure. On 11th February, 1873, the First Republic of Spain was proclaimed, and on 14th July the Canton of Murcia was inaugurated under the leadership of Antonete Gálvez.

This insurrectionist ideal followed on from similar events just a few days before in Cartagena, which would eventually be the last city on Spain to climb down from its self-proclaimed cantonal status.

In 1874 the Republican episode ended with the coup d’état led by General Martínez Campos, and the Borbón monarchy was restored. In Murcia the situation returned to the pre-revolutionary state of affairs, with the upper and middle classes strongly supporting the restored monarchy.

Ups and downs in the early 20th century

At the start of the 20th century, the Murcian bourgeoisie underwent a series of generational changes, and the brightest light in the city was perhaps Juan de la Cierva Peñafiel, who was to become Mayor of the city, with a network of local officials supporting him. Only with the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera did the star of De La Cierva begin to wane.

The Second Republic was proclaimed on 14th February, 1931, with the victory of the reformers and radicals leaving the Murcian conservatives in a precarious position. The church came to their aid, offering political support to create the Murcia Popular Action group, which was the basis of the reorganization of the right wing for the elections of 1933. In the elections the conservatives presented a united front, and won representation in the Republican government.

Another election in 1936 was won by the Republicans, but in July of the same year General Franco carried out his coup d’état and the Civil War began. This eventually ended in victory for Franco.

Franco’s Dictatorship and its effects on Murcia

The lack of machinery, the loss of dynamism in the market, the international trade blockade and the interventionist policy of the State in agriculture all combined to result in years of shortages and rationing in Murcia.

Relations with the outside world did not start to improve until 1953, and international isolation ended. Between 1960 and 1975 there was a sharp increase in mechanization and in the use of fertilizers in agriculture, which led to increases in industrialization, productivity, and profitability. It was at this time that the first Urban Land Use Plans were drawn up, although they remained largely theoretical documents which were never put into practice. In 1979 the plan of Manuel de Ribas Piera received official approval, and it is this document that has shaped recent urban development in the city.

The crisis in agriculture freed up the workforce for employment in various industrial and service sectors, generating a migration from rural areas towards the city, which expanded in order to accommodate the new population.

After the death of Franco in 1975, the municipality participated along with the rest of the country in the transition to democracy and the formation of the Autonomous Communities.

The municipality of Murcia and rapid urban growth

On 25th May, 1982, the Statute for the Autonomy of the Region of Murcia was passed by the national parliament, and Murcia became one of the seven Autonomous Communities consisting of just one province.

On 25th May, 1982, the Statute for the Autonomy of the Region of Murcia was passed by the national parliament, and Murcia became one of the seven Autonomous Communities consisting of just one province.

Within the Autonomous Community there are 45 municipalities, with Murcia itself being by far the most heavily populated, and one of the most modern and urban town halls.

Over the past thirty years Murcia has grown spectacularly, with the population of the municipality having trebled in the course of a generation. There are currently over 440,000 inhabitants, making it the seventh largest city on Spain in terms of population. More than half of these live in the 54 “pedanías”, or outlying areas, some of which have become important towns in their own right, and a significant number own detached houses on small plots of land in the Huerta.

Murcia these days is a thriving metropolis, the capital of the Autonomous Community, a communications hub and the home of a prestigious university. From inauspicious beginnings as a Roman villa, after centuries of ups and downs, and despite numerous natural disasters, Murcia is now a forward-looking and prosperous city which embraces the future with optimism, while remaining fiercely proud of its past.